The Location of the Swedish Delivery Wards

When looking for a new place earlier this year, I had to take into account the time it would take me to get to a delivery ward (förlossningsavdelning) from there. It was a bit cumbersome to check since I was looking at multiple cities, so I decided to make a map in three easy steps:

-

Get the list of all the Swedish hospitals that have a delivery ward

-

Find out from which areas one can reach those hospitals within 30, 60, and 120 minutes

-

Put the areas on a map.

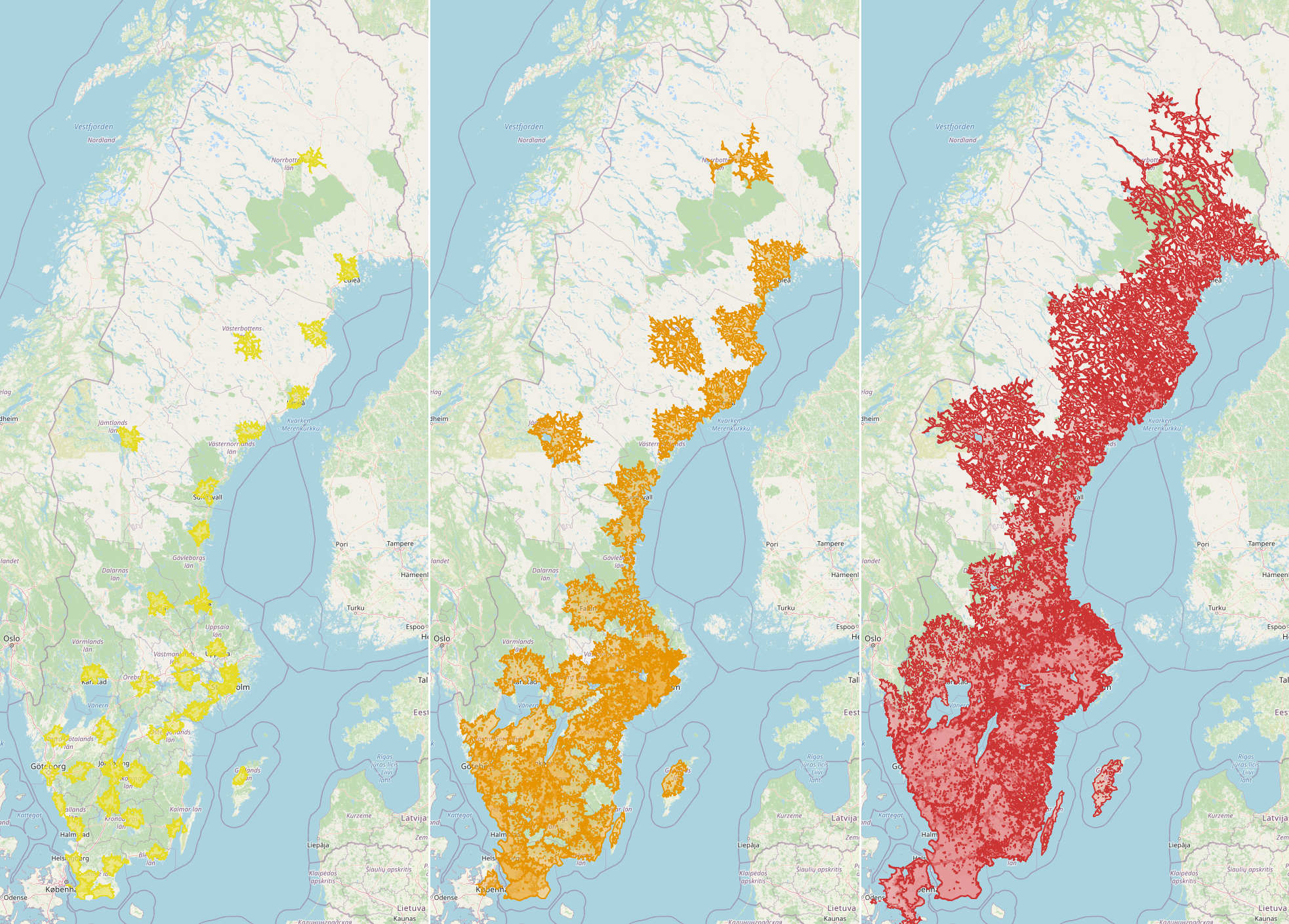

These are the results: half an hour, an hour, and two hours. The image can be open in a new tab, it’s a bit bigger then.

Update: slow but interactive (with zoom in/zoom out) versions for: 30 minutes, 60 minutes, 120 minutes (the last one often fails to load, unfortunately).

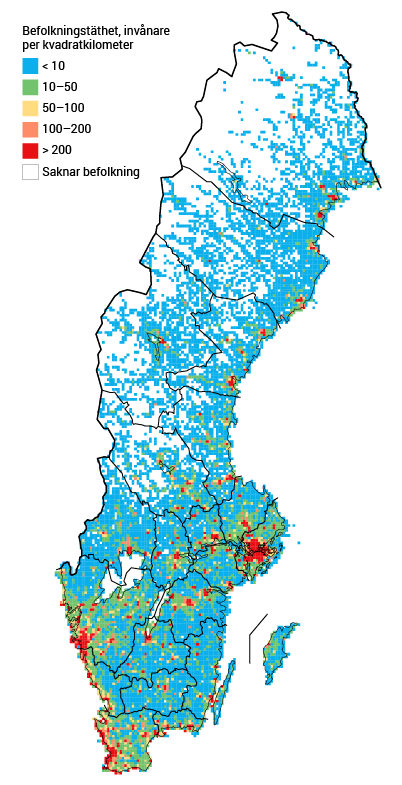

A map of the population density from Statistics Sweden (aka SCB):

At least two delivery wards were closed down in the last five years: one in Sollefteå (Västernorrland) in 2016, and one in Karlskoga (Örebro län), in 2019. If on the day you need it the closest delivery ward is full (which is more likely during the summer, I read somewhere), you will be told to go to another one. This can even happen in Stockholm, apparently, which has multiple delivery wards; in this interview, a Swedish tv presenter tells a story of her second child’s birth. There weren’t any free places anywhere in Stockholm, so she got redirected to Gävle (that’s about 170 km to the north by E4).

Technical notes for very dedicated people

The guiding principle I used when making the maps was “throw together the first things that seem kinda fitting”. Below are some technical details about those things.

Getting the coordinates of all the delivery wards

This part was manual as hell. I started with using 1177.se’s “Hitta vård” function, but somehow it did not show me all the förlossningsavdelningar. In the end, I used a recent article from Swedish public television to get all the relevant hospitals, and went through them one by one, using their websites to determine where exactly the delivery ward is (bigger hospitals have multiple buildings). Shout out to Skåne’s hospitals that make it very easy to find this information.

All the coordinates ended up in a dictionary in my Python script.

Finding out the areas

This part was less manual, but still more manual than I had anticipated. There’s this beautiful service called TravelTime which exposes an API for getting exactly this sort of data. You just POST a request and get a simple json back. The pricing is in the hundreds and thousands of GBP per month, but luckily it’s possible to get a free API key for a short trial. Since I only needed to make a few requests, it fit perfectly.

Except of course not. First I found out that each request to the API can only contain ten searches. Fair enough. The free trial key is limited to ten requests per day and 14 days; I needed to check 44 hospitals × 3 time limits (half an hour, one hour, two hours), which means 132 searches in total. 132 searches divided into batches of ten to fit into a request ⇒ 14 requests is enough. I can make 10 requests per day ⇒ two days is all I need, not counting testing.

Except of course not. On some days of my trial, I would get three responses back, and the rest of my requests would be met with an error about surpassing the daily limit. Other days it was more than three, and sometimes it was fewer. At some point I added a pause between my requests. This had no effect whatsoever. The alerts about approaching the daily limit sometimes came and sometimes didn’t. I have no idea what kind of eventual consistency was at play here, but in the end I just modified my script to keep track of the successfully completed searches and retry the rest every morning until I got them all. It took considerably more days than two.

Anyway, the documentation of the API was pretty good, and the examples helpful. Most importantly, the data returned looked accurate.

Putting shapes on a map

My search for things to do with a json full of longitudes and latitudes brought me very quickly to Tom MacWright’s blog I already know and love. I skimmed through this post about GeoJSON to get a feeling for it, added about ten lines to my script to transform TravelTime’s response json:s into GeoJSON:s, and proceeded directly to poking geojson.io. It’s slick.

As the last step, I used another tiny script to add 'properties': {'stroke':

'#<some_color>', 'fill': '<some_other_color>'} to the geojson files so that

the maps are not so uniformly grey. The end!

There is no comments section, but if you'd like to give feedback or ask questions about this post, please contact me.