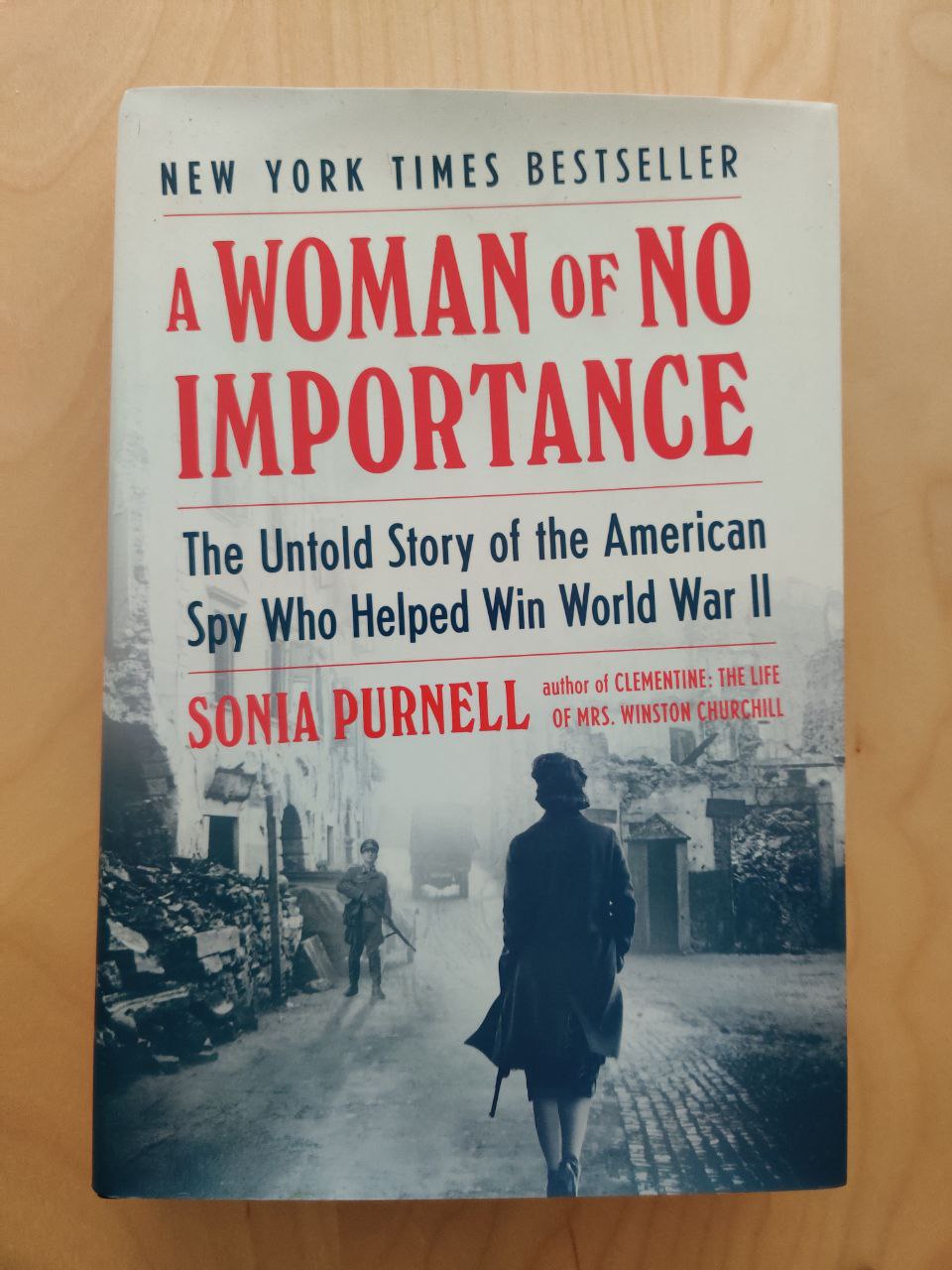

A Woman of No Importance: The Untold Story of the American Spy Who Helped Win World War II by Sonia Purnell

One of biographies of Virginia Hall, a spy in World War II.

This is a tale about grit. Virginia has a prosthetic leg and lives in America, where Nazi Germany is not an immediate threat; nobody really thinks she, being a woman, can be of any value as a spy; and yet, she ends up running a huge spy operation in the occupied France.

Nothing about war is smooth or pretty, so the pages fill up quickly with danger, torture, lost friends, as well as reckless allies putting everyone’s life in danger for the sake of booze or women, and good old discrimination. The two most astonishing miracles described in the book are (1) Virginia’s perseverance and (2) her ending up in low-level desk jobs again and again no matter what she achieved before. Amazingly, her gender is more of a problem than her disability. Nobody’s perfect, I guess.

The woman drives an ambulance under fire, gets into a new section of British secret service, goes undercover in France, builds up a vast network from zero with little to no support, runs logistics for everything from papers to bombs, and never stops or complains. She gets some training before going undercover, but it doesn’t seem like most of what she does in the field comes from any source other than her own character and wits.

Many dissidents made it too easy; to Virginia’s continual horror they met in public, talked loudly and proudly, did not check out new recruits, used their own names, and fought with rival groups. […] As a mere liaison officer, she had no control over the actions of other groups, but when it came to recruiting her own people she sought to create a more secure and disciplined system of small, discrete cells of handpicked members prepared to follow orders.

The first members of her network include nuns of a convent, prostitutes of a brothel, and a local police chief. She creates a real organization spanning more than one city — and eventually it becomes too big and too successful to fly under the radar. Virginia, of course, refuses offers to pull out and go to safety. It goes on like this, with crossing proverbial and literal mountains, getting people out of prison, fighting. Eventually there is a betrayal, and unlike in the movies, it is catastrophic, but not the end of the story.

The end of the story is employment in CIA and retirement.

Finally, she was offered to work on a task that, insultingly, entailed her reporting to a male officer two ranks her junior. […] An unnamed senior officer blocked any hopes of promotions with a scathing end-of-year appraisal for 1956 despite admitting that he had never actually overseen her work. […] He posted the damning report immediately before going on leave, denying her the chance to discuss it. […] Even the CIA later recognized that she had more combat experience than most male officers, including five consecutive directors, and had been highly decorated for it too.

It always rubs me the wrong way when thoughts and feelings are attributed to a historical figure without some reference. This happens time and again in this book, which is all the more weird since it’s also highlighted more than once that Virginia was a private person, did not like to discuss war, did not talk about it much. It’s not too bad though, and the book is an engaging read overall.

★★★★☆

(368 pages, ISBN:9780735225299, Worldcat, Open Library)

There is no comments section, but if you'd like to give feedback or ask questions about this post, please contact me.